State of research

The Push-out Score™ is based on practical experience and academic research.

In academic research, it remains an open question whether CEO turnover can be reliably classified as forced/voluntary, disciplinary/normal retirement or expected/unexpected.

No reliable way

Weisbach (1988), Mikkelson and Partch (1997), Denis et al. (1997), and DeFond and Park (1999) argue that there is no reliable way to classify the motive for management changes.

Fee et al. (2015) note: “As is well known, it is often difficult to determine the identity of the party initiating a CEO change and the true reason for the event. Given the coveted nature of the CEO post and our sense of the data, we suspect that most CEO turnover is involuntary and represents a negative outcome for an executive, except in a subset of cases when the individual is near retirement age.”

Forced or voluntary?

A common categorization procedure is to use some variant of the Parrino (1997) algorithm.

Parrino classifies CEO turnover as forced or voluntary.

In Parrino (1997), the classification is based on the following decision process: first, a succession is classified as forced if the Wall Street Journal reports that the CEO is fired, forced from the position, or departs due to unspecified policy differences.

Under the age of 60?

For the remaining cases, the succession is classified as forced if the departing CEO is under the age of 60 and the Wall Street Journal announcement of the succession:

(1) does not report the reason for the departure as involving death, poor health, or the acceptance of another position (elsewhere or within the firm), or

(2) reports that the CEO is retiring, but does not announce the retirement at least six months prior to the succession.

The circumstances surrounding the departures of the second group are further investigated by searching the business and trade press for relevant articles to reduce the likelihood that a turnover is incorrectly classified.

Comparable position elsewhere?

These successions are reclassified as voluntary if the incumbent takes a comparable position elsewhere or departs for previously undisclosed personal or business reasons that are unrelated to the firm’s activities.

The Parrino (1997) algorithm has often been varied and supplemented.

Scandals, probes, class action lawsuits?

Maharjan (2015), for instance, starts with using the criteria of Parrino (1997), with some modifications, to classify the turnover as voluntary or involuntary: All turnovers for which the press reports that the CEO is fired, is forced out, or departs due to difference of opinion, pressure from shareholders or union, or unspecified policy differences with the board are classified as forced.

In addition, turnovers due to the board not renewing the contract, and turnovers triggered by scandals, probes, or class action lawsuits are also flagged as forced.

Announcement at least two months prior to the departure?

Of the remaining turnovers, if the departing CEO is under the age of 60, it is classified as forced if either:

(1) the reported reason for the departure does not involve death, poor health, or acceptance of another position elsewhere or within the firm (including the chairmanship of the board), or

(2) the CEO is reported to be retiring but there is no announcement about the retirement made at least two months prior to the departure, and the CEO declines to make any comments.

Comments regarding the departure?

Maharjan (2015) then complements these criteria with a few of his own.

He reclassifies a forced turnover (identified through the steps described above) as voluntary if either:

(1) the press does not specify any reason for the departure or there are no press reports on the departure, and the CEO’s employment record, obtained from BoardEx and Marquis Who’s Who publications, suggests that the CEO obtained a comparable position elsewhere within three months, or

(2) the press reports convincingly explain that the departure is due to previously undisclosed personal or business reasons that are unrelated to the firm’s activities, and/or the departing CEO steps forward to make comments regarding the departure.

All of the CEO successions not flagged as forced are classified as voluntary.

Rough classification

The algorithm suggested by Parrino (1997) has become more or less the standard approach to assessing whether a particular turnover is “forced.”

The Parrino algorithm only allows a rough classification: voluntary or forced.

Risk of misclassification

Hermalin and Weisbach (2017) state that a plus to the Parrino (1997) algorithm is “the turnovers it identifies as forced are likely correctly classified; a minus is it will mis-classify as voluntary those turnovers in which the press fails to report information about pressure exerted on executives to resign.”

Fee et al. (2015) point out that the Parrino (1997) algorithm “assumes that news article revelations of a forced departure automatically qualify a turnover event as forced.”

They further note that “[i]n the absence of such a revelation, the default choice is to treat young (old) executives who depart from the firm as forced (voluntary), using age 60 as the dividing line.”

Systematic biases

Fee et al. (2015) argue: “While this approach has intuitive appeal, it may contain some systematic biases. In particular, holding constant the actual reason for the departure, the press may be more likely to label any given departure as forced when absolute or relative firm performance is poor, leading to spurious inferences. In addition, since news revelations of overtly forced departures are rather rare, this algorithm relies heavily on a CEO’s age, treating a 59 (60) year old who departs as almost surely forced (not forced). At the very least, detailed age modeling/controls should be incorporated into models that use this algorithm.”

Fee et al. (2015) use additional information regarding the forced versus voluntary nature of a given type of event.

They categorize CEO turnover as generic, severance-payment, and overtly forced turnover.

“Generic turnover” includes all CEO changes with the exception of health/death/acquisition/jump events.

“Severance-payment turnover” includes all CEO changes with the presence of a payment to the departing CEO (e.g., severance payment, consulting agreement).

“Overtly forced turnover” includes all CEO changes where the CEO was fired, ousted or forced from the position, according to press reports.

Partially forced and partially voluntary

Furthermore, in our view, reality is complex. Turnover may be partially forced and partially voluntary.

“Half drew him in, half lured him in.”

(Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

The line between the five categories of termination:

- layoff (termination due to elimination of a position, forced),

- discharge due to performance (forced),

- disciplinary dismissal (termination for cause, forced),

- retirement (termination caused by age, mandatory or voluntary) and

- resignation (termination on the initiative of the employee, voluntary)

may be blurred. A decision to classify a departure as voluntary or forced is subject to discretion. Deductive methods may lead to misclassifications.

Deductive

Deductive reasoning goes from the general (the theory) to the specific (the observations). For example, “All CEOs can be fired. Jim is a CEO. Therefore, Jim can be fired.” For deductive reasoning to be sound, the hypothesis must be correct.

Deductive conclusions are certain provided the premises are true.

If the generalization is wrong, the conclusion may be logical, but it may also be untrue.

For example, the argument, “All departing CEOs who are over the age of 60 are leaving voluntarily. Jim is over the age of 60. Therefore, Jim is leaving voluntarily,” is valid logically but it is untrue because the original statement is false.

The following premises are also questionable:

- All departing CEOs who are under the age of 60 and accept another position elsewhere or within the firm are leaving voluntarily.

- All departing CEOs who announce the retirement at least six months prior to the succession are leaving voluntarily.

Inductive

Inductive reasoning goes from the specific (the observations) to the general (the theory).

We make as many observations as possible, discern a pattern, make a generalization and infer an explanation or a theory.

Inductive arguments reach probable conclusions.

Another strength of inductive reasoning is that it allows us to be wrong. It is only through more observation that we determine whether our premises are true.

Plato and the kangaroo

This strength is also a weakness. Sometimes, observation possibilities are limited.

Plato was applauded for his inductively obtained definition of man as “featherless biped.” He had never seen a kangaroo.

Scoring model developed by exechange

For our purpose, an inductive approach appears to be particularly promising. A hypothetico-deductive approach would bring more disadvantages than benefits.

To assess management changes, exechange adopts a new, holistic and interdisciplinary approach.

Close interaction with our readers

Our methodology is inductive, data-driven and based on close interaction with our readers.

Our customers require comprehensive information about the reason for the management change and details regarding the executive-firm fit and potential manager-shareholder agency conflicts at the time of the departure.

Our readers include personnel professionals, global executive search and leadership consulting firms, executive coaching companies, management consulting firms, event-driven investment managers, corporate governance experts, private equity firms, banks and corporations.

Inspired by the push and pull factors theory in migration research

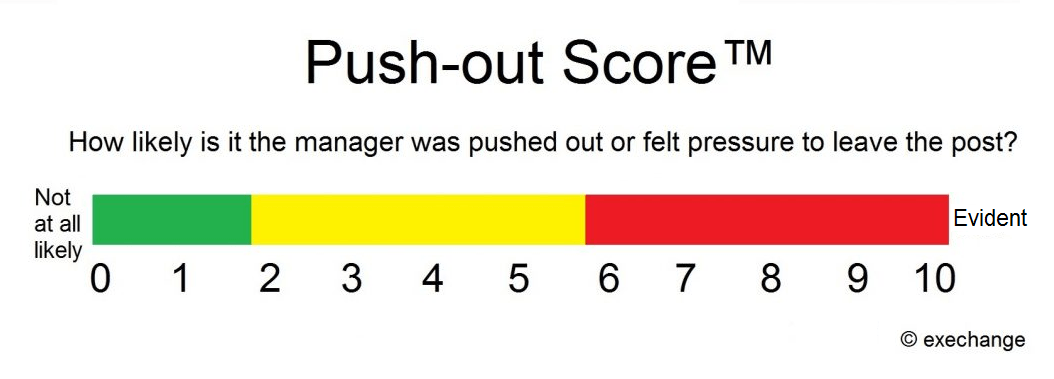

exechange’s scoring model is based on the assumption that management changes are triggered by pull-out forces and push-out forces.

The method was inspired by the push and pull factors theory in migration research.

Migration: Forced and voluntary

In migration research, two types of moves are distinguished: forced and voluntary.

According to the push and pull factors theory, migration is fueled by a combination of push and pull factors in place of origin and destination.

“Push-out force” and “pull-out force” are technical terms primarily used in engineering mechanics.

exechange’s scoring model considers

- age,

- notice period (time between announcement and actual departure),

- tenure,

- share price development,

- official reason given,

- circumstances of the management change (e.g., firm and industry performance, peer group performance, severance payment, consulting agreement),

- succession (internal vs. external) and

- several soft factors (e.g., language, form and structure of the announcement).

Quantity, quality and constellation

The final result of our analysis is a certain number of signs of push-out forces.

The quantity, quality and constellation of the signs enable a more sophisticated view of a complex situation.

To give an example, it is highly likely that a CEO (or CFO) has been pushed out or felt pressure to leave the post when at least six of the following nine criteria are met:

- The departure is buried deep within a big corporate announcement.

- The language in the announcement is icy.

- The age is under 60.

- The departure is effective immediately.

- The tenure of the executive is under three years.

- The recent share price performance is poor.

- The reason for the departure is not given or not transparent (e.g., “to pursue new opportunities,” “to spend time with the family,” “for personal reasons”)

- The company reports bad news on the same date (e.g., weaker-than-expected results).

- A permanent successor is not immediately available.

Our research stands up to outside scrutiny and meets the requirements of our readers and customers.

References

DeFond, Mark L. and Chul W. Park, 1999, The effect of competition on CEO turnover, Journal of Accounting and Economics 27, 35-56.

Denis, David J., Diane K. Denis and Atulya Sarin, 1997, Ownership structure and top executive turnover, Journal of Financial Economics 45, 193-221.

Hermalin, Benjamin E. and Michael S. Weisbach, 2017, Assessing managerial ability: Implications for corporate governance. Forthcoming in The Handbook of the Economics of Corporate Governance.

Fee, C. Edward, Charles J. Hadlock, Jing Huang and Joshua R. Pierce, 2015, Robust models of CEO turnover: New evidence on relative performance evaluation, Working paper, Tulane University, Michigan State University, University of South Carolina, and University of Kentucky.

Maharjan, Johan, 2015, Essays on executive turnover, Retrieved from Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations, Paper 419.

Mikkelson, Wayne H. and M. Megan Partch, 1997, The decline of takeovers and disciplinary managerial turnover, Journal of Financial Economics 44, 205-228.

Parrino, Robert, 1997, CEO turnover and outside succession: A cross-sectional analysis, Journal of Financial Economics 46, 165-197.

Weisbach, Michael S., 1988, Outside directors and CEO turnover, Journal of Financial Economics 20, 431-460.